– that’s all you need to know

19

News India Times

May 1, 2015

Special Report

By Beenish Ahmed

A

bout every 30 minutes, a

farmer in India commits

suicide. The unseasonably

heavy rains and unexpected

hailstorms that have pounded

down across the country threat-

en to up that already alarming

figure.

According to one expert, a

sudden downpour of hail in the

Indian state of Maharashtra laid

waste to more than $150 million

worth of crops.

One farmer there didn’t even

wait for the March storm to

abate. After seeing his crops col-

lapse into the mud, 27-year-old

Sandeep Shinde hung himself

from a tree in his field, leaving

behind his wife and two young

children.

“I cannot even afford milk for

the children,” his widow, Shoba,

told the Times of India.

Farmer suicides are doubly

devastating because they mark

the death of a bread winner, and

often mean the loss of a season

of crops as well.While Prime

Minister Narendra Modi

increased compensation to

farming families who have lost a

loved one to suicide, the vast

majority of those promised gov-

ernment aid claim they haven’t

received it, even 20 years on.

According to state govern-

ment records, there have been

40 percent more suicides in

Maharashtra in the last seven

months than during the same

period last year. Similarly har-

rowing reports have come from

other parts of India.

So far this year, 12 farmers in

the state of Bengal and more

than 36 farmers in Uttar Pradesh

have killed themselves.

In the 20 years since the

Indian government first started

keeping track of farmer suicides,

about 300,000 farmers have

ended their own lives. According

to the 2011 census, the suicide

rate for farmers is 47 percent

higher than the national average.

That rate is even higher in the

United States where male farm-

ers are twice as likely to commit

suicide than the general popula-

tion.

While the phenomenon is oft-

discussed in India, it’s not limit-

ed to the South Asian state.

Farmers around the world have

turned to the suicide amid crops

failures and livestock diseases. A

recent Newsweek article called

the phenomenon an “interna-

tional crises.” Its author, Max

Kutner, pointed to several coun-

tries where farms have been

devastated by suicide:

In France, a farmer dies by

suicide every two days. In China,

farmers are killing themselves to

protest the government’s seizing

of their land for urbanization. In

Ireland, the number of suicides

jumped following an unusually

wet winter in 2012 that resulted

in trouble growing hay for ani-

mal feed.

In the U.K., the farmer suicide

rate went up by 10 times during

the outbreak of foot-and-mouth

disease in 2001, when the gov-

ernment required farmers to

slaughter their animals. And in

Australia, the rate is at an all-

time high following two years of

drought.

While the increased rates

Kutner cited for farmer suicide

are often tied to exceptionally

difficult years for farming,

experts, advocates, and industry

leaders have all put forth their

own reasons to attribute India’s

“epidemic” of farmer suicides to

one issue or another. But in real-

ity, the driving force behind the

bleak phenomenon is a complex

array of intertwining issues

make farming an increasingly

precarious vocation in India.

Vandana Shiva, India’s most

prominent environmental

activist, believes genetically-

modified seeds – specifically,

those sold by the agricultural

behemoth Monsanto – are driv-

ing farmers to lose control of

their own farming practices.

She’s claimed that the frustra-

tions over Monsanto’s propri-

etary policies which forbid farm-

ers from planting, selling, or

even accidentally growing seeds

fromMonsanto’s patented crops

push farmers to the brink. Shiva

and other environmental

activists have come to refer to

Monsanto seeds as “suicide

seeds.”

In 2013, she explained her

argument, citing one of

Monsanto’s genetically-modified

cotton seeds as an example.

“Monsanto’s seed monopo-

lies, the destruction of alterna-

tives, the collection of superprof-

its in the form of royalties, and

the increasing vulnerability of

monocultures has created a con-

text for debt, suicides and agrari-

an distress which is driving the

farmers’ suicide epidemic in

India,” Shiva wrote. “This sys-

temic control has been intensi-

fied with Bt cotton. That is why

most suicides are in the cotton

belt.”

But many researchers have

started to take issue with the

notion that genetically-modified

crops like Monsanto’s Bt cotton

are to blame for India’s epidemic

of farmer suicides. Some have

pointed out that Indian farmers

continued to purchase

Monsanto seeds even as activists

railed against them – and for

good reason: because it proved

profitable to do so.

For its part, Monsanto has

argued that its crops require less

pesticide purchase and less loss

of yield —meaning that farmers

who opted for its genetically-

modified seeds would be more

successful than those who use

traditional seeds.

But Shiva has countered,

claiming that Monsanto drove

up the price of seeds 8,000 per-

cent – and that “the high costs of

purchased seed and chemicals

have created a debt trap.”

Since debt is a major cause to

farmers’ despair, however, it’s

not just agricultural companies

like Monsanto who are responsi-

ble. For those seeking loans to

pay higher up-front costs for

Monsanto seeds, unfair lending

practices increase their financial

woes.

Anoop Sadanadan, a profes-

sor of political science based at

Syracuse University, has argued

that farmer suicides should be

attributed not to agricultural

practices but rather financial

ones. In a paper published last

year, he noted that farmer sui-

cides were concentrated in five

of India’s 28 states – and that

those five offered the least insti-

tutional credit to farmers, forc-

ing them to take out private

loans at interest rates as high as

45 percent.

Government policies towards

agriculture may also bear a part

of the blame for imposing addi-

tional hardship on farmers – or

rather, for suddenly stopping to

insulate them from it. The rate at

which farmers committed sui-

cide saw a spike in 1997 – the

same year that the government

removed subsidies for cotton.

Climate change has increas-

ingly been cited as a major cul-

prit to farmer suicides in India.

Although it’s a difficult trend to

measure, farmer suicides tend to

increase along with extreme

weather phenomenons. And

extreme weather is becoming

more and more common in

India.

In 2013, Germanwatch’s

Global Climate Risk Index

ranked India as one of the three

countries affected by the most

extreme weather events in 2013.

The sort of sudden downpours

that has wrought havoc on the

country’s cotton belt, are on the

rise. Scientists have found that

they’ve increased by 50 percent

over the last 50 years. Scientists

believe that such devastating

events will only increase. India’s

Intergovernmental Panel on

Climate Change has predicted

that “rainfall patterns in penin-

sular India will become more

and more erratic, with a possible

decrease in overall rainfall, but

an increase in extreme weather

events.”

Often, years with the most

calamitous weather mean hikes

in farmer suicide. In 2009, for

example, more than 17,000

farmers killed themselves – a six

year high, according to the

National Crime Records Bureau.

That year India saw the worst

drought it had seen since 1972.

Its affects may still be felt by

farmers. Devinder Sharma, of

the New Delhi-based Forum for

Biotechnology and Food

Security told theWall Street

Journal in 2009, “The severe

drought has pushed back the

household economy of farmers

in the rural areas by 10 years.”

Six years later its effects may

still be being felt in unbearable

ways.

– Think Progress

Behind India’s ‘Epidemic’ Of Farmer Suicides

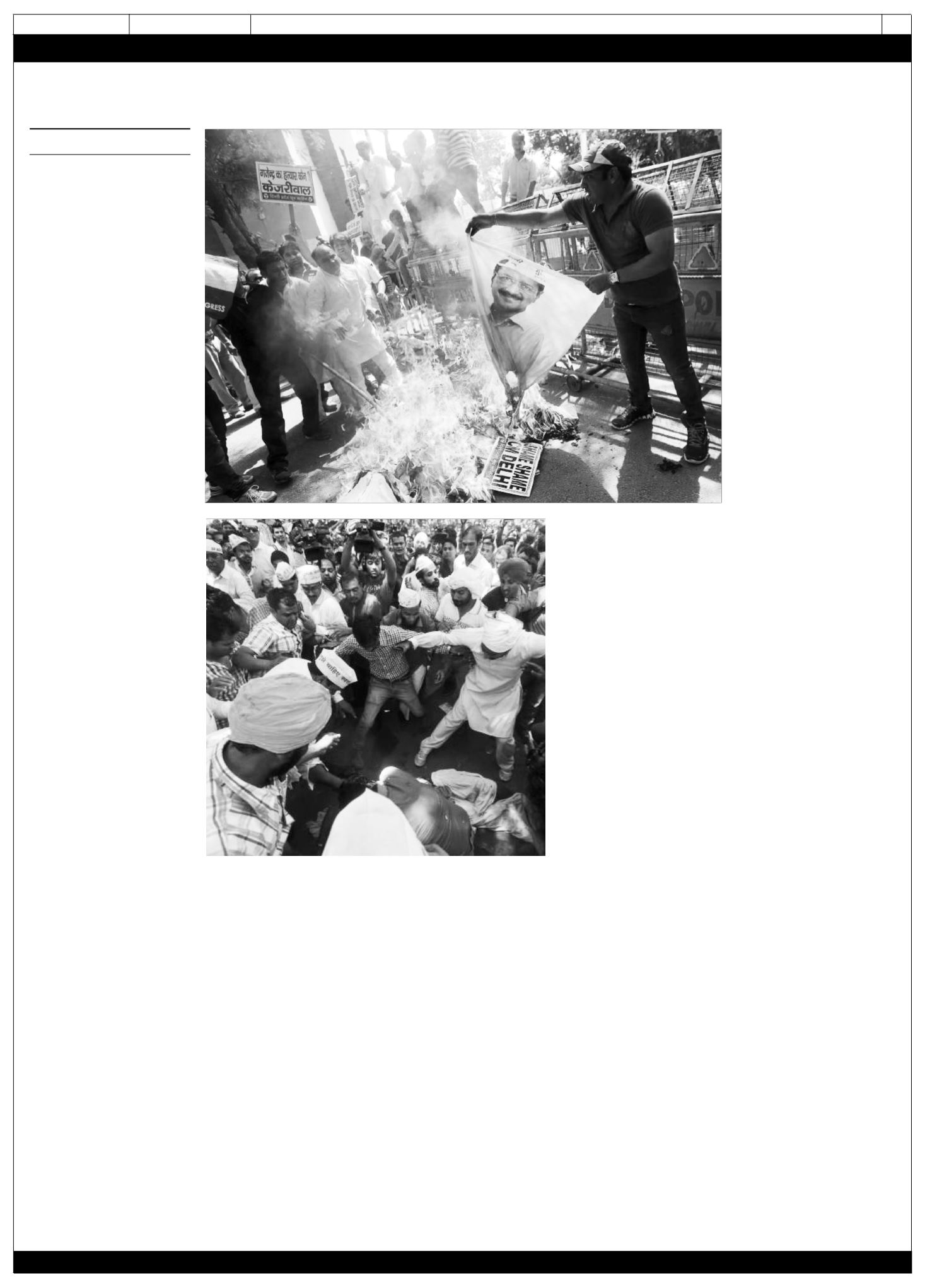

Above, an activist of the youth wing of

India’s opposition Congress party burns a

banner of Arvind Kejriwal,

chief of Aam Aadmi (Common Man) Party

(AAP) and chief minister of Delhi, during

a protest over the April 22 suicide

by a farmer at a rally April 23, in New

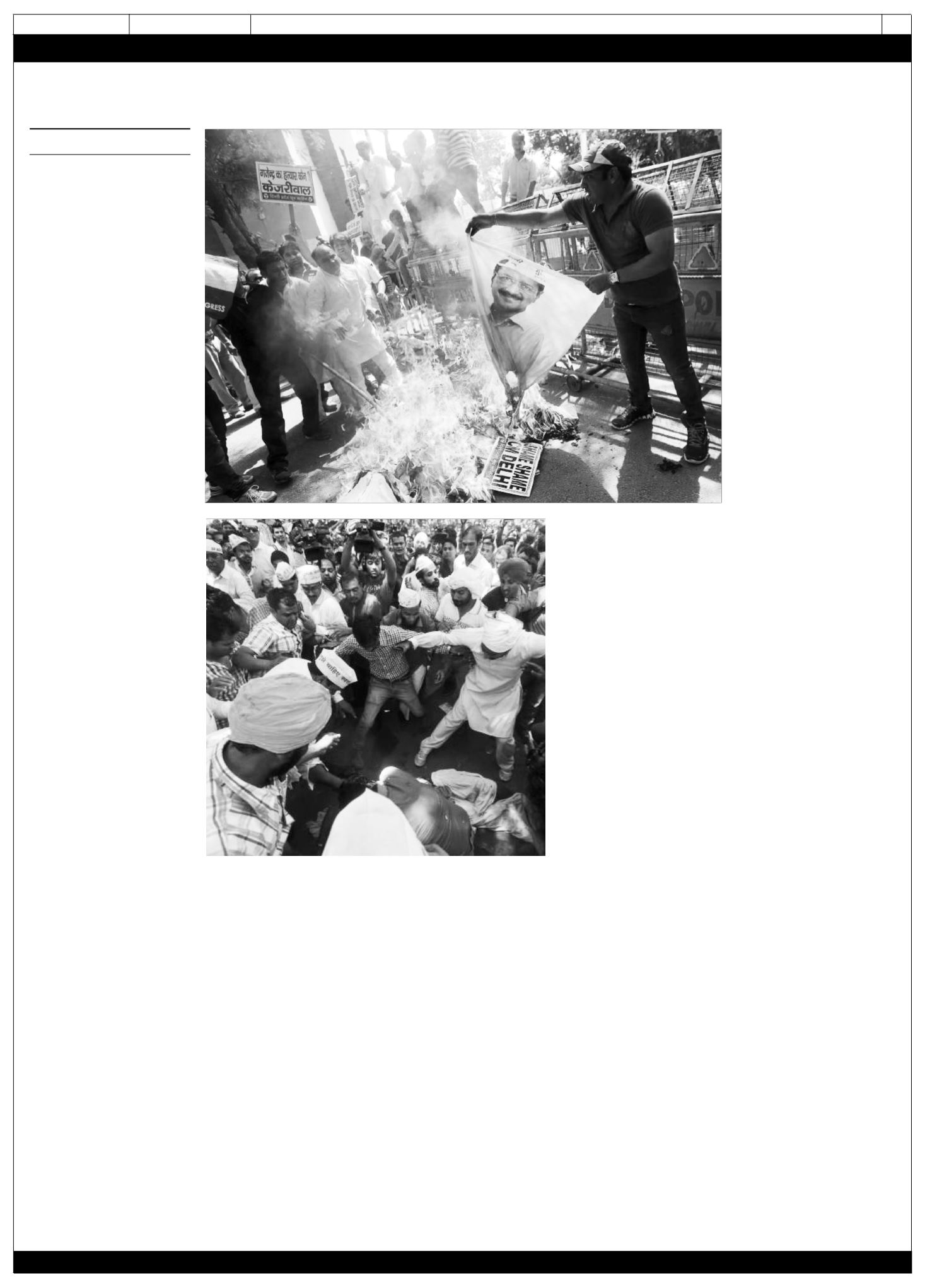

Delhi. Left, protesters gather around a

farmer who hung himself from a tree dur-

ing a rally organized by AAP, in New Delhi

April 22.

Reuters