News India Times

October 9, 2015

16

– that’s all you need to know

Cover Story

ByMarguerite Rigoglioso

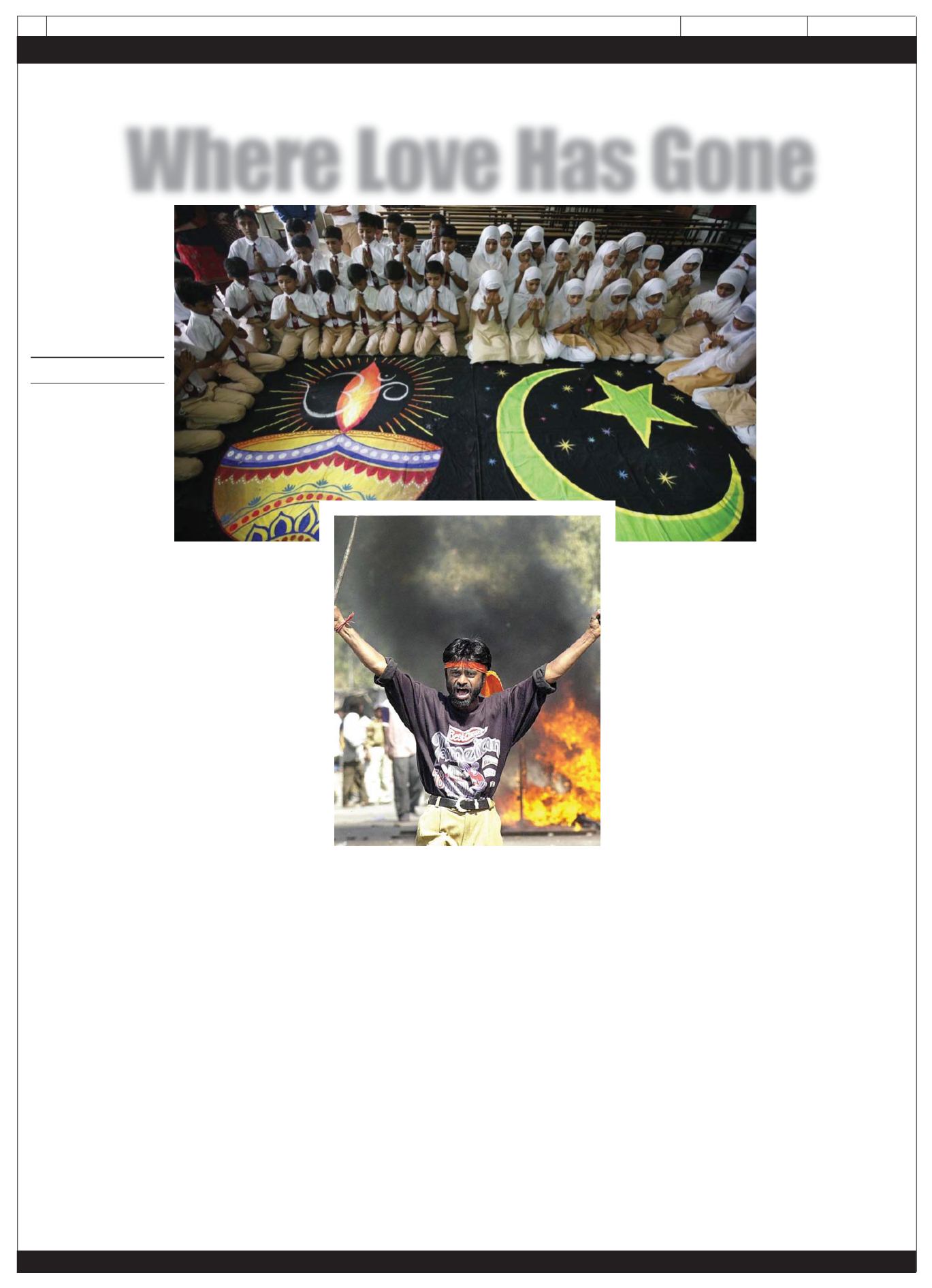

n recent years, as ten-

sions between Hindus

and Muslims have

mounted, India’s gov-

ernment has been

accused of instigating or

condoning numerous acts

of violence against

Muslims.

Popular thought in

India holds that the origin

of this conflict goes back

centuries to medieval

times, when Muslims

expanded into the Indian

subcontinent.

According to Audrey

Truschke, a Mellon post-

doctoral fellow in the

Department of Religious

Studies, however, much of

the current religious con-

flict in India has been

fueled by ideological

assumptions about that

period rather than an

accurate rendering of the

subcontinent’s history.

In her new book,

Culture of Encounters:

Sanskrit at the Mughal

Court (Columbia

University Press, forth-

coming), Truschke says

that the heyday of Muslim

rule in India from the 16th

to 18th centuries was, in

fact, one of “tremendous

cross-cultural respect and

fertilization,” not religious

or cultural conflict.

In her study of Sanskrit

and Persian accounts of

life under the powerful

Islamic dominion known

as the Mughal Empire, she

provides the first detailed

account of India’s religious

intellectuals during this

period.

Her research paints a far

different picture than

common perceptions,

which assume that the

Muslim presence has

always been hostile to

Indian languages, religions

and culture. A leading

scholar of South Asian cul-

tural and intellectual his-

tory, Truschke argues that

this more divisive interpre-

tation actually developed

during the colonial period

from 1757 to 1947.

“The British benefited

from pitting Hindus and

Muslims against one

another and portrayed

themselves as neutral sav-

iors who could keep

ancient religious conflicts

at bay,” she says. “While

colonialism ended in the

1940s, the modern Hindu

right has found tremen-

dous political value in con-

tinuing to proclaim and

create endemic Hindu-

Muslim conflict.”

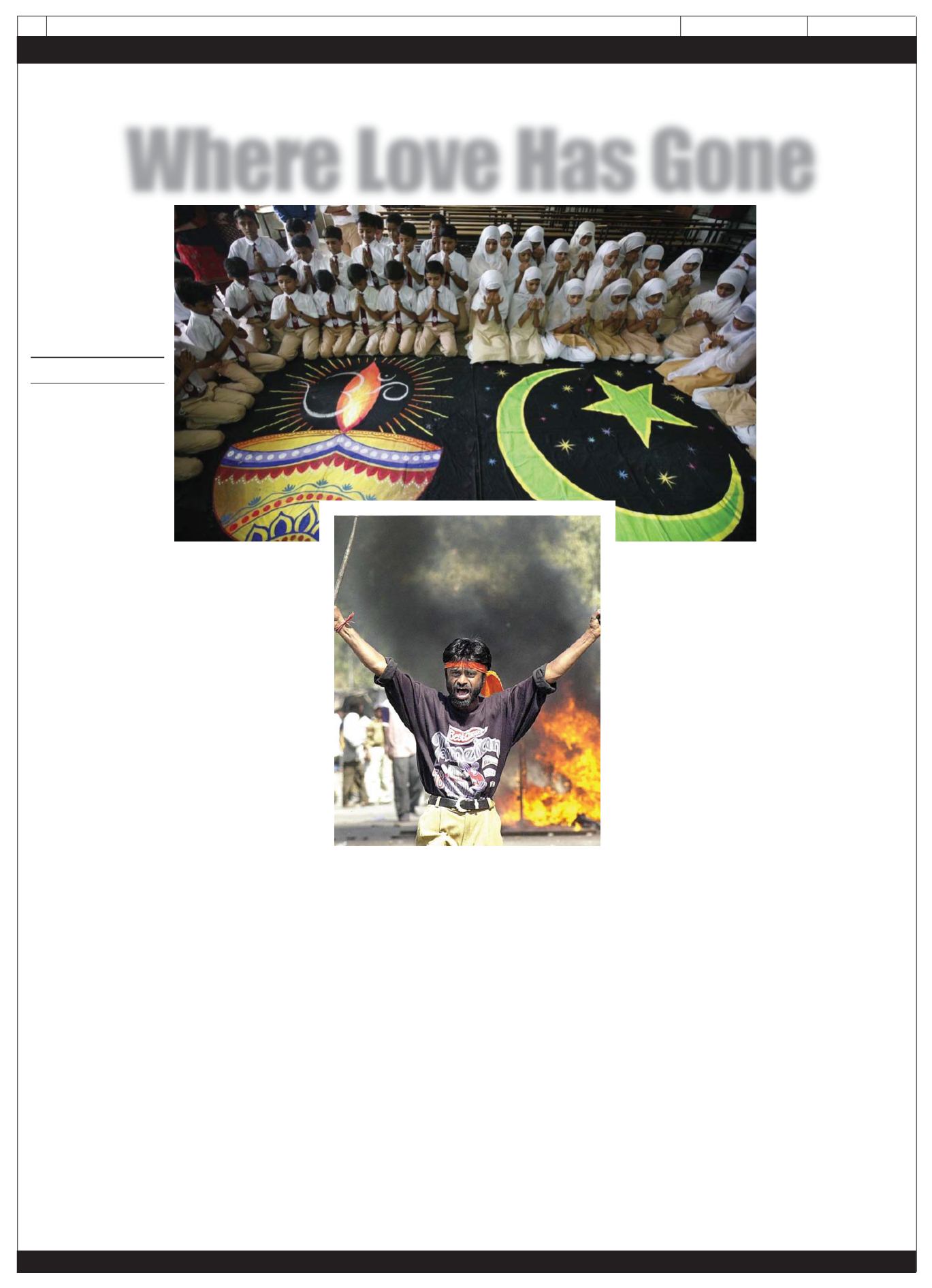

Prime Minister

Narendra Modi’s Hindu

nationalist Bharatiya

Janata Party has been criti-

cized for being anti-

Muslim. Modi was chief

minister of Gujarat state,

where in 2002 Hindu mobs

killed more than 1,000

Muslims; he was widely

blamed for failing to stem

the violence. As a result,

the United States denied

Modi a visa for more than

a decade until 2014 when

it became clear that Modi

would be India’s next

prime minister.

Truschke argues that

the ideology underpinning

such violence – one that

Modi himself openly

embraces – erroneously

“erases Mughal history and

writes religious conflict

into Indian history where

there was none, thereby

fueling and justifying

modern religious intoler-

ance.”

Her work shows that the

Muslim impulse in India

was not aimed at dominat-

ing Indian culture or

Hinduism. She hopes her

findings “will provide a

solid historiographical

basis for intervention in

modern, political rewrit-

ings of the Indian past.”

Correcting The Record

Truschke, one of the few

living scholars with com-

petence in both Sanskrit

and Persian, is the first

scholar to study texts from

both languages in explor-

ing the courtly life of the

Mughals. The Mughals

ruled a great swath of the

Indian subcontinent from

the early 16th to the mid-

18th centuries, building

great monuments like the

Taj Mahal.

Over several months in

Pakistan and 10 months in

India, Truschke traveled to

more than two dozen

archives in search of man-

uscripts. She was able to

analyze the Mughal elite’s

diverse interactions with

Sanskrit intellectuals in a

way not previously done.

She has accessed, for

example, six histories that

follow Jain monks at the

Mughal court as they

accompanied Mughal

kings on expeditions,

engaged in philosophical

and religious debates, and

lived under the empire’s

rule. These works collec-

tively run to several thou-

sand pages, and none have

been translated into

English.

Truschke found that

high-level contact between

learned Muslims and

Hindus was marked by

collaborative encounters

across linguistic and reli-

gious lines.

She said her research

overturns the assumption

that the Mughals were

hostile to traditional

Indian literature or knowl-

edge systems. In fact, her

findings reveal how

Mughals supported and

engaged with Indian

thinkers and ideas.

Early modern-era

Muslims were in fact

“deeply interested in tradi-

tional Indian learning,

which is largely housed in

Sanskrit,” says Truschke,

who is teaching religion

courses at Stanford

through 2016 in associa-

tion with her fellowship.

Hybrid Political Identity

Truschke’s book focuses

on histories and poetry

detailing interactions

among Mughal elites and

intellectuals of the

Brahmin (Hindu) and Jain

religious groups, particu-

larly during the height of

Mughal power from 1560

through 1650.

As Truschke discovered,

the Mughal courts in fact

sought to engage with

Indian culture. They creat-

ed Persian translations of

Sanskrit works, especially

those they perceived as

histories, such as the two

great Sanskrit epics.

For their part, upper-

caste Hindus known as

Brahmins and members of

the Jain tradition – one of

India’s most ancient reli-

gions – became influential

members of the Mughal

court, composed Sanskrit

works for Mughal readers

and wrote about their

imperial experiences.

“The Mughals held onto

power in part through

force, just like any other

empire,” Truschke

acknowledges, “but you

have to be careful about

attributing that aggression

to religious motivations.”

The empire, her research

uncovers, was not intent

on turning India into an

Islamic state.

“The Mughal elite

poured immense energy

into drawing Sanskrit

thinkers to their courts,

adopting and adapting

Sanskrit-based practices,

translating dozens of

Sanskrit texts into Persian

and composing Persian

accounts of Indian philos-

ophy.”

Such study of Hindu

histories, philosophies and

religious stories helped the

Persian-speaking imperial-

ists forge a new hybrid

political identity, she

asserts.

Truschke is working on

her next book, a study of

Sanskrit histories of

Islamic dynasties in India

more broadly.

Indian history, especial-

ly during Islamic rule, she

says, is very much alive

and debated today.

Moreover, a deliberate

misreading of this past

“undergirds the actions of

the modern Indian nation-

state,” she asserts.

And at a time of conflict

between the Indian state

and its Muslim popula-

tion, Truschke says, “It’s

invaluable to have a more

informed understanding

of that history and the

deep mutual interest of

early modern Hindus and

Muslims in one another’s

traditions.”

– Stanford Report

I

Where Love Has Gone

Stanford Scholar Casts New Light On Hindu-MuslimRelations